Bill Belichick readily admitted that his offense would have to change with Tom Brady out of the picture.

"Over the last two decades," Belichick said back in April, "everything we did, every single decision we made in terms of major planning, was made with the idea of how to make things best for Tom Brady . . . Whoever the quarterback is, we'll try to make things work smoothly and efficiently for that player and take advantage of his strengths and skills."

For now, let's assume the quarterback in 2020 will be Jarrett Stidham. How can Belichick and Josh McDaniels make him comfortable? How can they make things work "smoothly and efficiently" for him?

We won't know for sure until the Patriots take the field. But emphasizing looks that have taken the league by storm of late, looks that have simplified things for good-but-not-great quarterbacks, looks that Belichick's pal Mike Shanahan is credited with popularizing... That might make things interesting.

The second installment of our "Stidham Plan" series takes a look at how a couple of newly-added tight end options might make the second-year quarterback's life a little easier.

* * * * *

This may seem counterintuitive, but it's true: If you want to be effective throwing the football, take a wide receiver off the field.

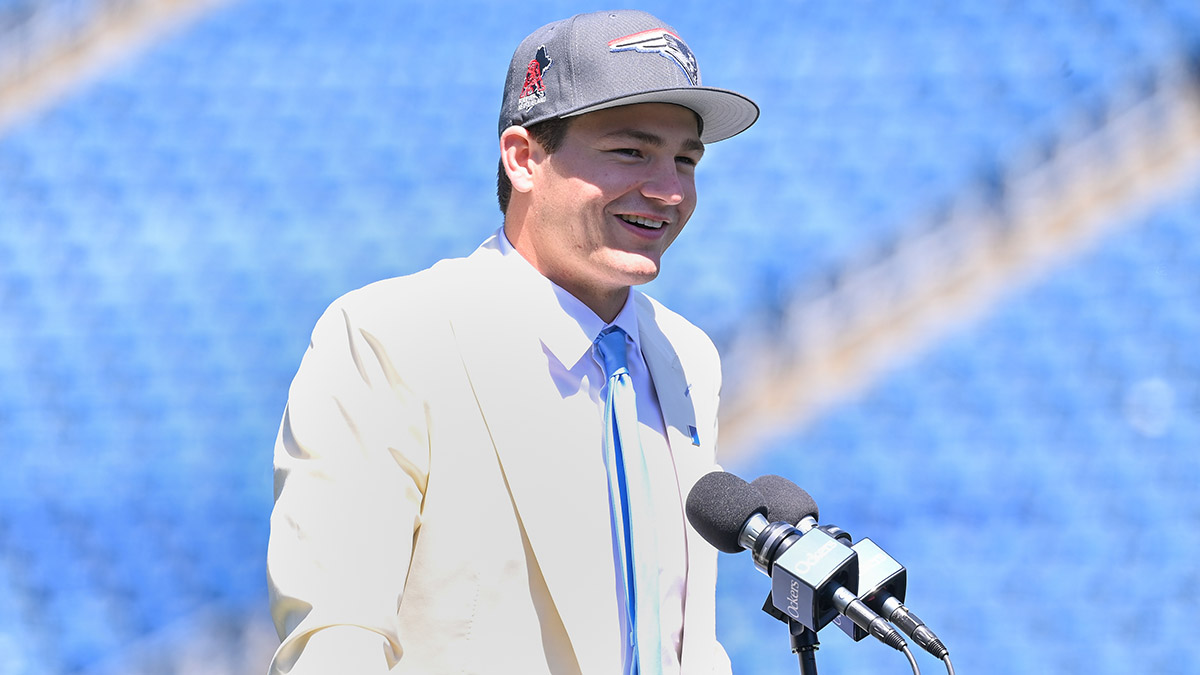

New England Patriots

That's a generalization. But, in general, in a league that uses three-receiver sets more often than any other, that's the reality. Want to be more efficient throwing the ball? Take one of your best pure pass-catchers off the field and sub in a fullback or a tight end. Your passing game will be better off.

Don't believe it? Check the numbers.

Teams ran 11 personnel (one back, one tight end, three receivers) on 60 percent of offensive snaps last year. They threw for 7.1 yards per attempt from those looks, and 44 percent of passes from those formations were "successful," according to Sharp Football Stats. ("Successful" meaning the play picked up 40 percent of the yards needed for a first down on first down, 60 percent on second down and 100 percent on third or fourth down.)

Download the MyTeams app for the latest Patriots news and analysis

Teams ran heavier 21 personnel looks (two backs, one tight end, two receivers) — a set we dug into from a Patriots perspective recently — on eight percent of offensive snaps last year. They threw for 7.7 yards per attempt on those throws and were "successful" on 52 percent.

The most popular two-receiver set to throw from last season was 12 personnel (one back, two tight ends, two receivers), which was used across the NFL on 20 percent of offensive snaps. Those throws averaged 7.7 yards per attempt (like 21 personnel) and were successful 49 percent of the time (more often than 11 personnel throws).

The same has held true each of the last several seasons. In 2018, teams averaged more yards per pass attempt and had a higher success rate when throwing out of "12" and "21" than they did throwing out of "11." Success rates when passing out of "12" and "21" were higher than "11" in 2017 and 2016 as well, per Sharp.

That's four years of information, thousands of plays, that would suggest the following: Bigger offensive people on the field, in general, equals better pass plays.

Thus, for a young quarterback like New England's Jarrett Stidham, it'd make sense for the Patriots to squeeze as much as they can from the two tight ends selected in the third round of this year's draft, UCLA's Devin Asiasi and Virginia Tech's Dalton Keene. Their presence on the field as versatile weapons — both have the ability to align as in-line players, in the slot or in the backfield — should produce some uncertainty in the minds of defenders.

How will they be used? How should they be matched? How those questions get answered could end up leading to mismatches in coverage and thus opportunity for a new starting quarterback.

If defenses mirror your tight ends with slower linebackers, chuck it and let them use their skills as receivers. If they mirror your tight ends with smaller defensive backs, hand it off and let them use their skills as blockers.

Before a game against the Eagles last season, Patriots safety Devin McCourty provided some insight into the mind of a defensive player forced to take on two effective tight ends simultaneously and the headaches those looks incur. The Eagles ran more 12-personnel plays than any offense in 2019.

"The two types of tight ends they have," McCourty said of Philadelphia's Zach Ertz and Dallas Goedert, "both those guys are 4.7, 4.6 (40-yard dash) guys. They run great routes. They split out wide. Whether you call it '12' with two tight ends — or is it '11' with three receivers? — they have that kind of versatility . . . I think because of their size and their skill set, they’re able to do a lot of different things from a versatility standpoint that you don’t see from a bunch of teams."

'DETROIT' IN NEW ENGLAND

Under Bill Belichick, the Patriots have historically been effective when utilizing two tight ends themselves.

Even before his Patriots tenure, Belichick was an early 12-personnel proponent. He helped those packages earn the nickname "Detroit" — a nickname still kicking around today — decades ago as an assistant for the Lions in the 1970s. The Lions had two tight ends at the time, Charlie Sanders and David Hill, who were tough covers. Together they helped upset Chuck Fairbanks' Patriots in Week 5 of 1976, 30-10.

According to Ian O'Connor's book, "Belichick: The Making of the Greatest Football Coach of All Time," it was Belichick who urged the Lions to try two tight end sets that week against New England's defense. Four years later, as an assistant for the Patriots, Bill Parcells learned to call two tight end sets "Detroit." The name stuck as Parcells' coaching tree branched out to include the likes of Charlie Weis, Al Groh and, of course, Belichick.

Belichick's best season using "12" came in 2011 when he and the Patriots redefined what was capable with two gifted athletes at the position. Rob Gronkowski and Aaron Hernandez, both second-year players, combined for record-breaking totals for receptions (169) and touchdowns (24) by tight ends that season. The Patriots also had above average success rates from "12" with Gronkowski and Martellus Bennett or Dwayne Allen in 2016, 2017 and 2018, per Sharp.

As part of a well-oiled short-to-intermediate passing game that emphasized the importance of having dependable options in the middle of the field, Belichick and his staff have long understood how to deploy 12 personnel effectively. Out of "12," staple concepts like "HOSS" — which fueled the game-winning drive for Super Bowl 51 — made mismatches easy to spot.

In 2019, though, with Gronkowski retired and no obvious fill-in, the Patriots became a below-average 12-personnel team when it came to their success rates in both the passing and running games.

So how can the Patriots try to recapture their "12" magic and help their young quarterback in 2020?

Listen and subscribe to the Next Pats Podcast:

THE BLUEPRINTS

There's a scheme that's been propping up quarterbacks across football we've homed in on lately, and it just so happens that scheme functions well with two tight ends on the field. It's the old Mike Shanahan Broncos attack that's undergone some alterations in different locales and is featured in San Francisco (under Kyle Shanahan), Minnesota (under former Mike Shanahan assistant Gary Kubiak), Los Angeles (under former Mike Shanahan assistant Sean McVay), Green Bay (under former Mike Shanahan assistant Matt LaFleur) and Tennessee (under former LaFleur assistant Arthur Smith).

Every team runs its own variation. The Niners nearly won a Super Bowl favoring 21 personnel, but they're no strangers to multi-tight end looks. The Titans rode "12" to one of the most efficient passing games in football last season. The Vikings can easily roll with "12" or "21," but used two tight ends more frequently a season ago.

All of them center around the "wide-zone" running game with passes built off of that wide-zone action. With multiple backs or tight ends on the field in that scheme — and, in theory, more linebackers on the field to stop the run — play-action fakes can help buy receivers several seconds to get open and quarterbacks several seconds to find them. That kind of time, more than an offense would typically have on a straight drop-back pass, yields numbers.

Proof? Ryan Tannehill led the NFL in quarterback rating off of play-action for the Titans in 2019 (143.3). Minnesota's Kirk Cousins was fourth (129.2) and tied Lamar Jackson for the NFL lead for touchdowns thrown off of play-action (14). San Fran's Jimmy Garoppolo was sixth in yards per attempt off of play-action (10.8) and fifth in touchdowns (9).

Buoyed by their play-action performances, Tannehill, Garoppolo and Cousins all ranked in the top 10 in the NFL in overall yards per attempt (first, third and seventh, respectively) and quarterback rating (first, eighth and fourth, respectively).

Those three quarterbacks also played in above-average passing games with 12 personnel on the field thanks in part to their play-action passing convepts. They checked in with yards per attempt figures of 7.8 (Vikings), 8.2 (Niners) and 10.7 (Titans) out of those looks when the league average was 7.7. With two backs and two tight ends on the field together — 22 personnel — the yards per attempt numbers for the Niners (11.1) and Vikings (8.7) were well above average (7.6).

If the Patriots want to employ some Shanahan principles more often this season and reap some of the passing-game rewards, deploying heavier offensive personnel and calling for hard play-action, they have the personnel to do it. They traded up for two tight ends in the draft, including one player they wanted badly enough that they made the rare move to trade a future pick in order to secure him.

They also added a dynamic athlete at fullback who could provide a different element as a receiver than what the Patriots had for years with James Develin.

If Josh McDaniels wants to go with a 12-personnel package, he has Asiasi and Keene. If he wants a 21-personnel package, he can turn to Asiasi and put Danny Vitale (or Keene) in the backfield. If McDaniels wants a 22-personnel package, he could get all three players on the field simultaneously. Those heavier looks could lead to bigger-bodied defenders on the field, and all kinds of play-action opportunities for Stidham.

More time after the snap . . . wide-open throwing lanes . . . it's a young quarterback's dream.

ON THE GROUND

"The success of the offense," one AFC assistant from the Shanahan tree told me, "is all about the running game."

The running game in the Shanahan offense starts, in some ways, with the tight end position. That's where the running back is headed as soon as he takes a handoff for a wide-zone running play. Even before the ball is snapped, the back is looking at the tight end — and more specifically, the tight end's blocking assignment on the play — to get an idea of how his path will be altered.

If the defender can get "reached" by the tight end, meaning the tight end can get to the defender's outside shoulder and pin him inside, then the back will bounce outside.

If the defender is leveraged outside of the tight end and can't be reached, then the tight end will use his inside hand to shove the defender toward the sideline to clear a lane for the back to cut up and inside.

The two examples shown above happen to feature the best tight end in the NFL. But the Patriots don't necessarily need the next George Kittle to make these blocks work, unlocking these runs, and thereby opening up play-action off similar looks. But having someone with good athleticism and aggressiveness to try to turn good gains into explosive ones is critical.

If the Patriots want to use their rookies on the edge in wide-zone situations, they have those plays in their playbook. Early last season, though, they struggled to make them work.

The Patriots like tight ends who can get into blocks quickly, handle defensive ends one-on-one, and control the edges of defenses. They were lacking in that area without Gronkowski, and finished September with 22 outside zone runs that collected a total of 29 yards (including a two-yard touchdown run by Rex Burkhead).

In the running game, here's how Patriots tight ends finished against their peers, according to Pro Football Focus' run-blocking grades: Matt LaCosse ranked 37th, Ben Watson ranked 56th and Ryan Izzo ranked 81st out of 82 tight ends with at least 100 snaps last season.

Meanwhile, Asiasi or Keene appear to fit the blocking profile the Patriots are looking for at the position. League evaluators told NBC Sports Boston prior to the draft that both were among the best run-blockers — and among the most aggressive at the position — in the 2020 class. If they can absorb what they're fed by Josh McDaniels, that may open up the wide-zone running game for the Patriots, which could then pay real dividends for Stidham.

THROUGH THE AIR

Even if this particular scheme is centered around getting defenses to think about the running game first, what makes those wide-zone plays dangerous is what happens when the running back doesn't get the ball.

"It's gotta look like, taste like, smell like the run," Vikings offensive coordinator Kevin Stefanski told Tom Pelissero of NFL Network last season.

For wide-zone teams, when the quarterback is under center on early downs, flanked by heavy personnel, the defense has to buy in on the possibility that a run is coming. When linebackers or safeties bite on the inevitable run fake, that's when throwing windows open wide for quarterbacks.

Consider these numbers from PFF: The league average for first and second-down snaps taken under center over the last three years is 54.1 percent. The Vikings last season (their first with Kubiak on staff) were under center on a whopping 81.6 percent of their first and second-down plays. The Rams, under McVay since 2017, have been under center more than average at 68.4 percent of the time. The Niners under Kyle Shanahan are next at 66.5 percent over the last three seasons, and the Titans checked in last season at 62 percent.

Just starting with the right elements — the right personnel on the field, the right alignment for the quarterback — can go a long way in selling play-action and buying quarterbacks time. With play-action "keeper" plays as a staple of Minnesota's passing game, Cousins led all quarterbacks last season in average time to attempt (2.83 seconds), per PFF. Tannehill was second (2.76).

Sometimes getting four seconds or more behind the line of scrimmage, a quarterback has time not only to process his reads as he rolls away from where the run fake was headed. It allows receivers to uncover. Tight ends, too.

In this style offense, the tight end is much more than a decoy to sell the idea of the run. Depending on the player's athletic skill set and his ability to juggle information, the tight end can run a number of different routes on play-action bootleg passes. Short patterns, intermediate, deep . . . they're all found in these types of plays, and they're all options for the right player.

The shallow element is often handled by a tight end running across the formation, as is the case in the example below. But it can also feature a tight end at the rollout side of the play who fakes a block at the snap and then pivots toward the sideline.

The intermediate route, generally run 10-12 yards across the middle of the field, is another natural option for the tight end in this style of offense. As defenders flow with the run fake in one direction, the tight end cuts across their movement and across the field to open space. If the linebackers involved in the play bite too hard on the run possibility, it's extremely difficult for them to turn and run to recover. That means nice healthy throwing lanes for quarterbacks.

The deep element of these plays is not one that tight ends often take on. Kittle, though, is a rare breed. Typically the deep element is used to clear out a corner for the intermediate route to run to the resulting opening. That deep route might also threaten a deep middle safety and keep him in the deep part of the field, preventing the intermediate crosser from being jumped. If the safety jumps the intermediate route anyway, that leaves all kinds of room for the vertical option to operate.

One of the other benefits of this scheme is that on all of these routes, players have the ability to maximize their run-after-catch numbers. If a quarterback can hit them in stride, in space, with a chance to run through contact? That can lead to easy yardage. Three of the top five tight ends in average yards after catch in 2019 (minimum 25 targets) hailed from wide-zone heavy offenses utilizing hard play-action: Tennessee's Jonnu Smith (second), Kittle (third) and Green Bay's Jimmy Graham (fifth).

PIECES IN PLACE?

Based on their physical skill sets, Keene and Asiasi should not only represent upgrades at the tight end position in New England. They should be nice fits if the Patriots want to deploy some of these quarterback-friendly Shanahan-style concepts.

Both players are considered talented after-the-catch runners. Asiasi has what looks like rare body control for a player his size, and he averaged 5.6 yards after the catch per reception for UCLA, per PFF. According to one AFC tight ends coach, Keene is a "no regard for his health" kind of player who welcomed contact at Virginia Tech and then ran through it. Keene broke nine tackles on 59 catches and averaged 8.5 yards after the catch per reception during his career there, according to PFF.

For Belichick, who reportedly once told Browns scouts that a "good measure of [a tight end] is also what he does with the ball after the catch," his two most recent additions at the position look like good fits. We pegged both as being the best Patriots options in the class according to what was laid out in Belichick's old Cleveland wish list.

If Keene and Asiasi's work as blockers can help make the Patriots running game more effective — particularly the wide-zone runs already in the Patriots' repertoire — then that should help lead to play-action success, thereby giving both players a chance to show what they can do with the ball in their hands.

Though 12 personnel was not kind to the Patriots last season, it's not as though Belichick and McDaniels forgot how to use it. It's been one of the most quarterback-friendly packages across the NFL over the course of the last several seasons, and it's been especially helpful to offenses that have sprouted from the Shanahan tree.

Wanting to make things work more smoothly and efficiently for a new quarterback behind center, and with promising new pieces at tight end, it might make sense for the Patriots to join the NFL's wide-zone renaissance in 2020.